Good morning and happy Wednesday! To kick off the new Fashion in Film blog series, I've chosen to analyze the costumes worn by Queen Victoria in "

The Young Victoria." Let's jump right in!

The costumes in the film were designed by Sandy Powell, who also worked on films such as

Hugo,

The Other Boleyn Girl, and

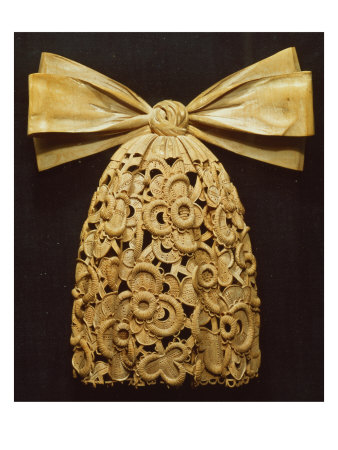

The Tempest. She says that near the beginning of the film, she wanted to give Victoria a more youthful look, since she's still under the control of her domineering mother. This shows in her pale yellow, flower-decked gown she wears for the king's birthday. The light fabric, lacy details, bow at the waist, flowers on the bodice and headpiece, and the general details of late 1830's formal wear all mimic a young girl's party dress.

The majority of Victoria's costumes for the first half of the film (even including the time between her coronation and marriage) reflect this almost childish aesthetic.

There are two costumes in "

The Young Victoria" which are based on actual garments: Victoria's coronation robe and her wedding dress.

Powell has said that the coronation robe was the hardest garment in the movie to create. The original robe is intricately embroidered, and in order to replicate that, the Wardrobe department screen printed the design onto a fabric that they custom-dyed.

Victoria's coronation garb does not particularly exemplify the fashions of the late 1830's. The ornate, luxurious details are timeless and nod to the long line of the monarchs of Great Britain. In addition, the v-waist, elbow length sleeves, and ornate over skirt that reveals a simple dress underneath suggests (at least to me) the mid to late 18th century, a time when the monarchs of the House of Hanover were at their prime (Victoria was the last British monarch of the House of Hanover, so this allusion may have been intentional. Or maybe it's just me. I haven't the foggiest).

The second costume in "

The Young Victoria" that is a replica of an actual garment is Victoria's wedding gown.

The wedding gown is an excellent, simple example of early 1840's fashion, with a low, pointed waist, bell-shaped skirt, and puffed sleeves.

This museum display of Victoria's real wedding dress is almost exactly like the one in the film. One difference is the lace on the bottom of movie-Victoria's dress, which isn't on the real one. But looking at this photograph below, it seems as though the dress was either two pieces (with one plain skirt and one lace skirt worn with the same bodice), or Victoria was wearing a lace overskirt.

One noticeable difference between Victoria's real gown and the gown in the film is the cluster of flowers at the bodice, which is replaced with a simple brooch in the movie. This portrait may have been the basis for this change, using an identical brooch in place of the flowers.

Even though Victoria became Queen of England before she married Prince Albert, she really didn't gain independence from her mother until after her marriage. After this point in the film, Victoria's gowns become slimmer, more fitted, and more mature. The pale, muted colors she wore while under the control of her mother flourish into vibrant, bold hues. It's interesting to see how the change from 1830's fashion (youthful, overly decorated, fluffy, and pale) to 1840's fashion (simple, structural, striking, and mature) mirror Victoria's character journey.

The last costume Victoria wears in the film is a vibrant blue gown with lace trim and a low 1840's waistline. She pairs this with a striking tiara and what looks like the same brooch worn with her wedding dress.

The bold color and slim structure of the dress definitely reflect Victoria's strength of character, but to me, the lace accents also remind me of what she was when the film began and the journey she's made from the child ruled by a 19th century tiger mom to the strong, intelligent Queen of Great Britain.

So that wraps up our first Fashion in Film analysis! I definitely enjoyed putting this together. Join me next week as I dig into another fabulous lady's wardrobe.

Bonus round: Check out this article to see how actress Emily Blunt felt about wearing all of these gorgeous gowns.

Thanks to clothesonfilm.com and costumersguide.com for your lovely analysis, info, and pictures.